On Light & Liberty - 5786

The Lower East Side of New York City swarmed at the end of the 19th century. Journalist Jacob Riis famously reflected that you needn’t ask where you were, when entering the Lower East Side – the Yiddish signs, the Eastern European Kaftans, the bearded men with Yamulkes – this was “Jewtown.” The sidewalks were storefronts for bakers, butchers and clothiers. The streets were open-air markets where most of life’s necessities could be bought for pennies from peddlers with pushcarts - from “spectacles and suspenders, [to] cups and candlesticks, [to] pants and pickles.” The tenements where they lived doubled as home and sweatshop, with up to 12 men, women, and children working in a single room. The sheer volume of immigrant Jews in this little corner of New York City was overwhelming - in density and in smell.

It was here, on the stage of the Lower East Side, in 1895, that a famed German antisemite named Hermann Ahlwardt, set his sights on delivering a hate filled lecture at Cooper Union – an iconic Lower East Side institution, known for giving a platform to voices of progress, reform, and the pursuit of knowledge - like Abraham Lincoln. Now, it would platform an antisemite.

You can imagine the Jewish community’s panic and outrage. Jewish leaders rushed to the young police commissioner of New York. “You have to stop him. Ban the lecture. Don’t give him protection. Why should our tax dollars protect a man who hates us?”

The Police commission could have heeded their requests. He could have refused a police detail, leaving Ahlwardt vulnerable. He could have tried to censor him, and silence a divisive voice. But the commissioner saw an opportunity for a different path.

He ordered his deputy to bring him thirty Jewish officers, “The stronger their ancestral marking, the better,” he said. When the men were assembled before him, he explained their task: “I am going to assign you to the most honorable service you have ever done — the protection of an enemy, and the defense of religious liberty and free speech in the chief city of the United States. You all know who and what Dr. Ahlwardt is. I am going to put you in charge of the hall where he lectures, and hold you responsible for perfect good order there throughout the evening.”

The commissioner made it clear: they weren’t protecting Ahlwardt’s message of hate: “I have no more sympathy with Jew-baiting than you have. But this is a country where your people are free to think and speak and act as they choose in religious matters, as long as you do not interfere with the peace and comfort of your neighbors. And Dr. Ahlwardt is entitled to the same privilege.” Guarding him, the commissioner insisted, wasn’t a burden — it was an opportunity. “It should be your pride to see that he is protected. That will be the finest way of showing your appreciation of the liberty you yourselves enjoy under the American flag.”

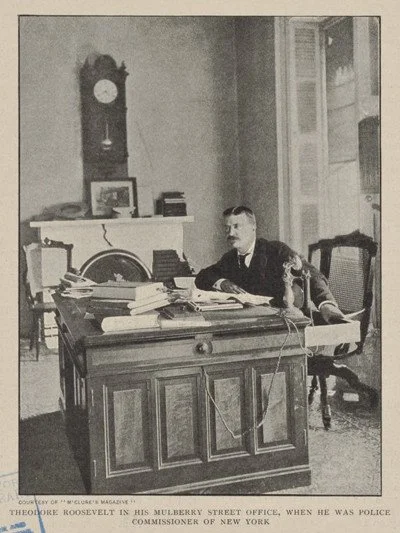

So on the second night of Chanukah, a team of 30 Jewish officers assembled at Cooper Union to maintain the peace for a German antisemite to spew hatred. The event went off without incident, save for a lone Jewish egg thrower whom the Jewish officers quickly escorted out. The commissioner’s plan succeeded — the Jewish officers made Ahlwardt look foolish, but more importantly, they defended the promise of their new country of liberty, of free speech, and of freedom of religion. In standing guard that night, they did more than protect a lecture hall; they lived out Isaiah’s prophetic claim to be a light unto their new nation, safeguarding America’s freedoms not just for themselves, but for the entire nation – even those who hated them. And that police commissioner…was soon-to-be President Theodore Roosevelt.

As historian Andrew Porwancher notes in his new book about President Roosevelt & the Jews, American Maccabee:

The episode would become part of Roosevelt's lore with the Jewish community. With great pride he routinely recalled how "Ahlwardt delivered his violent harangues against the men of Hebrew faith, owing his safety to the fact that he was scrupulously protected by men of the very race which he was denouncing." Roosevelt understood that the sight of Jewish policemen selflessly guarding the German Jew-hater did far more to undermine Ahlwardt's repugnant ideas than preemptive censorship ever could have. Reflecting on the incident years later in his autobiography, Roosevelt remarked, "It was an object-lesson to our people, whose greatest need it is to learn that there must be no division by class hatred, whether... of creed against creed, nationality against nationality, section against section.”

To immigrant Jews in the late 19th and early 20th century, the United States was “Di Goldene Medine” – the golden country – that Jews dreamed of when leaving their native lands for hopes of a better, safer future. For a Jew living in the Pale of Settlement, having experienced vicious pogroms by neighbors and police alike, it was nearly incomprehensible to live in a country where the police commissioner was not only on their side, but actively seeking to make the antisemite look like a fool.

And yet, antisemitism never disappeared from Jewish life in America, surfacing as different groups struggled for status within the nation’s social hierarchy. From the harassment of their fellow immigrant neighbors throwing stones and pulling beards to the elite of New York aristocracy peddling antisemitic tropes, creating quotas and furthering an anti-immigrant agenda, America has always been both hopeful and challenging to Jews.

This duality was captured by Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik in the mid-20th century, who used the biblical phrase “ger v’toshav” (the idea of being simultaneously stranger & resident) to describe the American Jewish experience. He reflected that, “We [Jews] are very much residents in general human society while, at the same time, strangers and outsiders in our persistent endeavor to preserve historic religious identity.”

The phrase Ger v’toshav comes from our Torah when Abraham sought a burial site for Sarah. He said to his neighbors: “Ger v’toshav anochi imachem – I am a stranger and a resident among you.” And this phrase, picked up on by Rabbi Soloveitchik neatly reflects the complexity of being Jewish in America – that even though we have been afforded the luxury of being at the table, a luxury seldom granted in Jewish history, we too, have always endured antisemitism here. And yet, we never let that stop us from working towards the American dream.

From the very beginning of our country, the days of Revolutionary America, Jews didn’t stand on the sidelines; we were involved, shaping the nascent country and insisting that liberty for all, meant liberty for us too. One of the most remarkable examples of this was Gershom Seixas — sometimes called “the Revolution’s Rabbi.”

Though he had no formal training, Seixas was appointed to lead New York’s only synagogue, Shearith Israel, at the ripe age of 22 – and you thought I was young. Without formal training, he went by many titles. At first Chazan, but when that didn’t catch on he went by Reverend, Pastor, and even The Priest. Writing to other Chazans in similar situations he referred to them as “Revd-Jew-Clergymen.”

In May of 1776, Revd-Jew-Clergyman Seixas heeded a proclamation from the Continental Congress meant for Christian clergy to organize a day of fasting and prayer. Seixas led his flock in worship, asking God to “put it in the heart of our Sovereign Lord, George the third…to turn away their fierce Wrath from North America.” Aside from calling on the “God of our Fathers Abraham Isaac and Jacob,” the prayer was as patriotic in tone as any of their Christian neighbors. In aligning his synagogue in patriotic prayer with the Nation’s churches, he insisted, as he would later write, that Jews should view themselves “as possessing equal rights and privileges with the rest of the inhabitants.”

Seixas’s courage earned him a place at George Washington’s first inauguration in 1789, where he represented the Jewish community. Shortly after that inauguration, President Washington visited Rhode Island and came into correspondence with Gershom Seixas’s older brother Moses. Moses was an established merchant, investor, and Freemason in Newport, and after the war, was elected to lead the Jewish community there in the famed Touro Synagogue.

Moses had grown up in a world where Jews were second-class at best, and often much worse. The Seixas family lore includes their ancestors who lived as conversos, or Jews forced to convert to Christianity in Spain and Portugal but secretly maintained some Jewish practices. One branch of the family is said to have escaped the Portuguese Inquisition in a laundry basket carried to the river under the nose of the Inquisitors, perhaps explaining the name given to the eldest and first American-born Seixas.

In 1790, Moses Seixas famously wrote to President Washington, acknowledging that Jews had been “previously deprived of the invaluable rights of free Citizens.” Seixas, though, was ready to use his post to forward their cause in the nascent American Republic. He lifted up the ideals of the Revolution and declared what America should mean: “a Government, which to bigotry gives no sanction, to persecution no assistance – but generously affording to All liberty of conscience, and immunities of Citizenship: deeming every one, of whatever Nation, tongue, or language, equal parts of the great governmental Machine.” Moses Seixas made clear his expectation that America could be a light unto the nations of the world — and that Jews, by living out our values here and contributing to the American experiment, would answer the Prophet Isaiah’s call to be a light.

The very next day, George Washington responded, and even echoed Moses Seixas’s own words. He wrote: “The United States gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance.” And then he reached for Scripture, promising that “the children of the stock of Abraham shall sit in safety under their own vine and fig tree, and there shall be none to make them afraid.” President Washington affirmed what the Seixas brothers hoped: that America would be a light unto the nations of the world.

Without the Seixas brothers, the story of Roosevelt on the Lower East Side a century later might never have been possible. They insisted that this new republic understood that liberty meant liberty for minority groups too - a lesson we are still learning, and still fighting for.

And so by the time Roosevelt ordered Jewish officers to protect an antisemite in 1895, he was acting within a civic tradition the Seixas brothers had helped secure for all Americans. We have always leaned into the American experiment — advocating for free speech, for free expression, for liberty itself — even as hatred against us and other minorities remains.

And perhaps that is the lesson for us today, as antisemitism and divisive rhetoric against minorities abounds: Do not retreat, but rather lean in and help America more fully realize its promise.

Earlier this year, when our community traveled together to Philadelphia,vwe stood before the Liberty Bell — cracked, imperfect, and still proclaiming its biblical vision from Leviticus: ‘Proclaim liberty throughout all the land, unto all the inhabitants thereof.’ As we walked through the city, we were reminded how short the American promise of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” has fallen. The American experiment is still going, and must be safeguarded, expanded, and renewed in every generation.

Many of us have never felt more like outsiders than we have over the past two years, displaced from our understanding of the American landscape and skeptical of safety we often took for granted in the United States. Antisemitism has found a home in mainstream discourse, and woven into it is a new wave of hostility toward Israel; not the justified criticism of policies or government actions, but the outright denial of Israel’s right to exist, and an ascription of responsibility placed on all Jews.

Beyond the struggles of American Jews, America at large is struggling: Kids murdered in sanctuaries, political figures assassinated, war expanding around the globe, immigrant communities gripped with fear as ICE mercilessly hunts down families for swift deportation, women losing control of their bodies and reproductive health, climate change exacerbating natural disasters. And…and…and…

It is easy to feel hopeless, to feel helpless, to feel despondent, every time we pick up our phones or read the news. And yet, we are also standing at a remarkable milestone of an event that led to unheard of safety and prosperity for our community: the 250th anniversary of the American Experiment.

This July 4th, we mark 250 years since the Declaration of Independence proclaimed that all people are created equal and endowed with the God-given rights to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” We know how short we have fallen of that promise — in slavery and segregation, in the exclusion and abuse of women, in the hatred and violence still festering today. And yet this anniversary is not only a moment to look back at founding ideals and reflect on our shortcomings, but and opportunity to come together in realizing our ideals and take an active role in shaping our future. “Imagine scores of people between now and next July moving from the cynical to the sacred, from argument to conversation. Imagine the most beautiful tapestry of potlucks and coffee klatches the nation has ever seen. Imagine people from all walks of life reading America’s most inspiring words and exploring them together. Imagine coming out of this national milestone more unified and more grounded in shared civic values.”

That is the vision of Faith250 — an interfaith initiative born from Reform colleagues in Virginia. Over the coming year, our own partnerships with First Presbyterian Church, and perhaps other Santa Monica congregations, will be dedicated to this project. And in the second half of the year, I will be teaching a course on American Jewish Civics, called Red, White & Jewish, to help us dig deep into our own texts and find inspiration for the civic ideals the founding Jewish patriots dreamed of.

This year, may we help our country fulfill what Moses Seixas once demanded from President Washington — a country that gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance.

May we live with the perspective of gerim, of strangers, of people who came out of slavery in Egypt to be a light unto the world, and may we lift up the voices of the vulnerable and defend their rightful place in the United States.

May we live, too, as toshavim, recognizing and using our privilege as American citizens to shape this nation for the good of all.

And like that company of Jewish officers on the Lower East Side, who guarded even an enemy so that liberty itself might be safeguarded, may we too stand watch: to defend democracy with courage, to breathe new life into America’s founding promise, and to ensure that freedom is not the privilege of a few but the right of all.

In the Sephardic tradition of the Seixas brothers, the greeting to the New Year is Tizku L’Shanim Rabot - May you merit many years. May our defense and pursuit of our shared American and Jewish ideals merit us a year of blessing, and may we all live up to the Prophet Isaiah’s call to shine a little light onto the darkness around us.